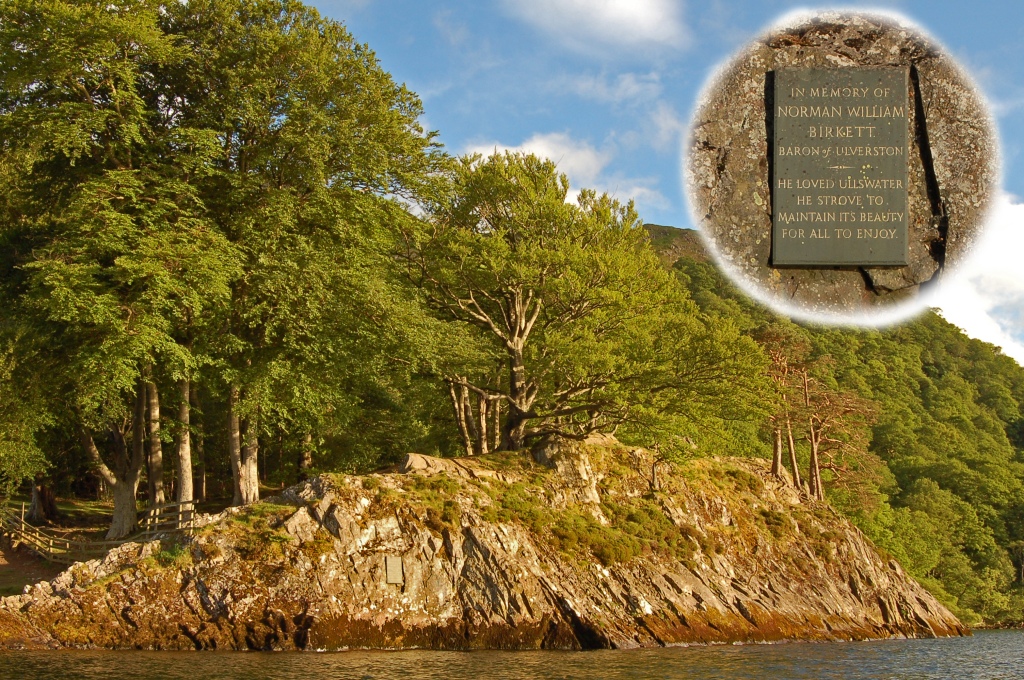

When Harriet and Rob Fraser wielded their creative genius to create an iconic art monument on the shores of Ullswater, they invented a new word to enter the English lexicon: treefold. If you walk the stretch of the Ullswater Way from Aira Force towards Glencoyne, you’ll come across one of three ‘treefolds’ that they established in the Lakes several years ago: treefold:north in Ullswater, treefold:centre in Grizedale Forest, and treefold:east on Little Asby Common. The treefold on Ullswater – the Long View – was inaugurated on 20th February 2018 with children from Patterdale Primary School. Stephen Dowson from the National Trust provided the oak seedling, whilst the children planted the seedling and afterwards sat on seats inside the treefold, within touching distance of the seedling, to contemplate their work. It was a wondrous moment for them – one which I’m sure they will never forget.

When you see it for the first time, it looks completely incongruous. An oak tree stands proudly in the middle of an exquisitely crafted circular stone wall. If you look closely at the wall, you’ll see, etched on the stone, facing the lake, some words: ‘The Long View’. These are the last words of a poem that flows between the three treefolds. We all know what a sheepfold looks like – an enclosure to protect sheep. What on Earth is the point of a stone wall around a tree? What a bizarre idea. Especially when you know that within several hundred metres of that spot, stand some magnificent old oak trees that have watched over this place for over 400 years.

On 1st July, as one of 8 participants in Harriet and Rob’s ‘Watershed Walk’ from Aira Force to Glenridding, we were treated to a magical moment when they confronted their very special monument, five years on. I was reminded of the celebrated tree hugging movement, that started in 1973 with the Chipko movement in India and spread across the world, notably Wangari Maathai’s Green Belt movement in 1977, which lead in 2004 to her being the first African woman to win the Nobel Prize.

We linked hands, and stood in silence, looking at the young oak and the sky, a moment of peace and reflection. It was a symbolic moment.

Although I had imagined the wall serving a protective function – like for sheep – this was not the way it was originally envisaged by Harriet and Rob. For them it was about ‘inviting people to pause with a tree while celebrating trees, for their own sake, and for what they provide for us and for other elements of an interconnected environment that is also rich in human cultures of stone wall building, stockmanship and woodland management… the relationship between people and trees, the bringing together of art and tradition, and the twinning of constancy and change’. (for more background read their link: https://www.somewhere-nowhere.com/portfolio/treefolds/).

The day had started at Glenridding pier, boarding the Lady Dorothy steamer. We were a motley group of amateur poets, writers, yarn spinners, and conservationists. We were participants in Harriet and Rob’s latest project: ‘Watershed: Bringing perspectives together – re-thinking relationships and processes of landscape change’.

It kicked off at a meeting in Glenridding Village Hall in March, bringing together a range of individuals, ‘sharing their concerns, joys and aspirations’ for the Ullswater Valley. The walk on 1stJuly will add to the collection of experiences that will be presented to the local community at Glenridding Village Hall on 19th July.

We gathered together on Aira green, at the end of the landing pier. Harriet pulls a piece of paper from her anorak, and reads her poem:

It puts us in the mood for the walk ahead.

We stop at Dorothy’s Gate, one of FOUW’s art works on the Heritage Trail, at the entrance to the Aira Force café. Time for another poem, this time from one of the participants, Barbara Hickson. When she retired she decided do a Masters in Creative writing. Suitably inspired, she’s already produced her first book of poems, and the second is on the way. This is what she read out to us: her poem ‘Hefted’

We walk past a truly magnificent veteran oak on our right hand side of the track, then on towards treefold:north. We break for lunch next to a stream, sheltering under a group of ash trees.

We come across another two veteran oaks. We pause to admire their amazing boughs, time to reflect. And time for some story – telling and word games. Harriet recounts their visit to Patterdale Primary School the previous week and the discovery that their new school mascot, following the recent death of Bob the Sheep, is . ….Bob the Raindrop. It takes over a year for that drop to travel from the beck next to their school, into Ullswater, then drift aimlessly the length of the lake before exiting into the River Eamont at Pooley Bridge and on to the sea. What a fantastic way for pupils to learn and understand the local ecology of the lake, the water cycle, through the daily travails of their raindrop mascot.We continue on past Glencoyne Farm and the bay where Donald Campbell first broke the world speed record on water on 23rd July 1955 (at 202 mph). It’s an area too, much favoured by painters such as JW Turner over the last 250 years (shortly to be celebrated by FOUW in its Ullswater Virtual Art Gallery, to be launched on 11th July).

We pass Stybarrow Crag and stop again at a fantastic vantage point, close to a WW11 gun emplacement, looking out over the lake, Place Fell and down the valley, past Glenridding. Karen, one of the participants, quietly perches on a rock and does a fantastic line drawing of the fells. Cecilia takes a skein of yarn out of her knapsack and starts spinning yarn from raw wool. She tells a worrying story how she and other yarn spinners have been grotesquely attacked by the social media.

Harriet dips into her rucksack and digs out some pieces of paper and pencils, and distributes them to all of us. She wants to hear of our Concerns – for Ullswater, the Earth, our Planet – up to us to decide, and write them down on one side of paper. On the other side she wants to hear our thoughts about the Future. I settle down at the base of an oak tree and start to ponder. How to summarise the Ills and Solutions of Ullswater and the World in 5 minutes? Food for thought. For the Future I come up with a word that I first came across whilst working overseas: the french word Épanouissement. There is no good English translation. The nearest you can get is: Flourishing/Blossoming. A world where every one and every thing blossoms.

Time to move on. We’re almost back in Glenridding. All of us somehow feel exhilarated. We’d like to meet again, maybe create a What’s App group. Maybe send each other thoughts, poems, words of wisdom about Ullswater. Open a space for creativity and reflection. Anyone can do it. Zero qualifications needed.

Many thanks Harriet and Rob. You’ve started a ball rolling ….

Tim Clarke, July 2nd 2023